The battery for one of my current creative endeavors ran out, seemingly spontaneously, and I’m annoyed. That could be a metaphor, but in this case, it’s literal. For my blog list item “Take a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) on Learning and Development,” I am doing a course created by the Exploratorium on the MOOC platform Coursera. The Exploratorium is a big deal in the world of interactive museum learning, particularly STEM. Every exhibit is hands-on, and almost all of them are open-ended, with no one goal to reach. This course, “Tinkering Fundamentals: Circuits,” explores tinkering as a learning tool. It builds off of work done in their tinkering studio (one of their education spaces) rather than the exhibits. It wasn’t my favorite MOOC experience, but it had a number of good resources, and brought up a lot of thoughts on tinkering as learning, which I’ll discuss here.

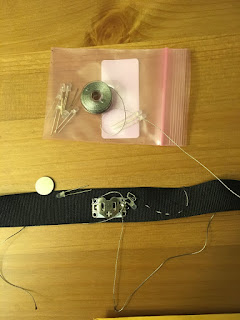

The biggest problem I had with the MOOC is that it’s no longer supported. Several of the links to readings are broken, including a reading that had been on the Exploratorium website. The course has a lengthy materials list so that participants can try each of the activities ourselves -- the projects include things like basic circuits to light up a lightbulb, “scribbling machines” made from a motor and markers, sewn circuits using conductive thread, and paper circuits using conductive tape. Several of the links in the materials list went to stores that no longer sold the part in question, so it was a lot more work than I expected to get set up. Some MOOCs are set up so that participants can do them any time, and others are run on specific dates, so that there are deadlines for the reading, and a group of people all respond to the discussion questions on a forum in the same time frame. This course is designed for the latter, but Coursera seems to just run it over and over again, setting new deadlines, etc. Not knowing to watch out for this, I assumed it was an active course, that there would be people in the discussion forums and that whether or not it was being led in real-time by an instructor, someone was doing basic maintenance on it. I was disappointed. The other frustrating thing was that they didn’t provide an estimated total cost for the materials. I ended up setting myself a $15 budget, and chose one activity to do. I ran over by about $5, getting things for sewn circuits. I chose the materials I thought I’d be most likely to use again after the course or to make something with that I might keep and use, which might be not a particularly tinkering-mindset way to do it, but a cost-effective one.

|

| Tinkering in progress |

I noticed while planning for the sewn circuits activity and shopping for materials that I don’t tend towards tinkering in my craft projects, at least not the way I think of tinkering. I tend to be goal-oriented. My main craft is knitting, with occasional crochet, sewing, chainmaille, etc. I don’t always stick to patterns, and I do design my own occasionally, but usually when I’m making something up, I have a particular outcome in mind and I’m trying different things I think will help me get there. I’m not trying different things for pure curiosity about what will happen. This course encourages trying things out of curiosity, but it doesn’t exclude my way from its understanding of tinkering. Instead, it talks about museum or classroom activities where students are encouraged to pursue “I wonder what happens if…” and also pursue their own goals, or “I wonder if I can get it to…” Still, I think encouraging more curiosity in the ways that I work wouldn’t be a bad thing. Until this course, I basically didn’t tinker with electronics. I did recently take apart a broken humidifier to see whether it was fixable (it wasn’t, at least not for less than the cost of replacing it) and now I wonder whether that was the course’s influence. One area in which I think I do (intangibly) tinker is writing -- I want things to come out well, but don’t necessarily know what I want the outcome to look like.

Something I really like about the course is its segments on “pedagogical perspectives,” talking about what’s going on in the learning process in the various activities. One idea that came up over and over again is that an essential skill for figuring things out is tolerating frustration. The course encourages teachers and activity facilitators not to step in right away when a student is frustrated. Given the opportunity to sit with a frustrating problem for a minute, they’ll often work through it on their own, building their capacity to sit with future problems. This doesn’t mean ignoring students when they ask for help, but it does mean not always giving them the answers, instead asking, “What have you tried so far?” or “why do you think it’s not working?” Anyone who has taught kids will be familiar with helping them go through the process of figuring something out rather than giving them the answer, but several teachers interviewed in the videos said it was especially hard while watching kids create things with circuits, perhaps because it’s such a hands-on activity.

Naturally, through much of the course, I made notes of what activities and principles I might be able to adapt for the medical museum where I work, especially when creating interactives. (Museum professionals have a habit of using “interactive” as a noun to mean “interactive activity” or “interactive exhibit component.”) I found myself running up against some internal resistance. In several activities I’ve worked on -- or supported while working in the galleries at other museums -- I don’t want the visitors to get frustrated for more than a few seconds. I picked up a saying from an app designer, I which I remembered who, “you have fifteen seconds before ‘never mind.’” Frustrated visitors will often walk away, especially when they have lots of distractions and choices for what to do. I think part of the difference is that I’m typically designing for completely unfacilitated experiences. In a classroom or workshop, the facilitator may deliberately not step in right away, but when someone is about to throw up their hands and walk away, the facilitator can say, “wait, we can figure this out. Walk me through your process, and where you’re stuck.” In a computer-based activity I’ve been working on at work, the program shows more detailed instructions after when the user gets something wrong, so they can try working it out for themselves first, but that’s not quite the same thing.

Another reason I felt some resistance to the idea that frustration is good is that I was doing a lot of the course at the same time that in my work life, I was working on an activity that isn’t open-ended. We had reasons for not making it open-ended -- it’s a walk-through of how nurses record medications in the medical records software, and we wanted to present the steps in their real-life order. It reminds me of a debate we had in one of my grad school classes: is every museum activity that’s hands-on interactive? We agreed probably not, because exhibits where you lift a flap to get more information or answer a question are hands-on, but we didn’t consider them interactive. Is everything that’s participatory interactive, or do you have to be able to make real decisions that change the course of the activity? On this one, we didn’t reach a consensus. The medication recording activity is hands-on and participatory -- visitors use a barcode scanner and the activity responds to what they try, but you can’t continue until you scan the right barcode. Are open-ended activities better, pedagogically? We didn’t quite debate that question in class, but I think it underlies a lot of discussions about museum interactives.

The tinkering course doesn’t argue that open-ended activities are better than all others, but makes a strong case that open-ended activities are excellent. I don’t disagree with that, at all! The course is making me think about what my goals are for the interactives I create, no matter where they are on the continuum from lifting a flap to exploring a tinkering studio. I’m not necessarily trying to get the visitors to become better learners and critical thinkers, even though that sounds like maybe it should be the ultimate goal of any educational activity. I think that often, my goals is to give people “aha!” moments where they can feel a new concept clicking in their brain. Ideally, an interactive will help them have more of an emotional response to the material than receiving it in a passive way -- sometimes that emotion will be the satisfaction and excitement that comes with the “aha!” and sometimes it’s more about empathy or curiosity. Have I ever designed an interactive that provokes empathy, though? To be honest, in the three years I’ve been creating content for museums as part of my full-time job, I’ve only created about three interactive things; they’re time-consuming! I believe that some kind of emotional response or feeling that mental click helps museum visitors remember the material better, care more about it, and be more likely to think of it when integrating additional new concepts into their knowledge. There’s research to support this, but I think it has become part of my philosophy or even dogma of learning, as well. None of that relies on an activity being open-ended or tinkerable, but being open-ended enhances it.

I'm nearly done with the course, and I'm enjoying playing with (tinkering with) the conductive thread, and LED lights. I'm planning to eventually turn this tinkering into a ribbon-based belt. The problem with playing with electronics that isn't true in, say, writing, is that when something stops working, I can't just move on to another section and come back to it. The battery I bought that fits in the sew-on battery holder is dead, and now I can't really move forward until I get a new one. In the meantime, here are some pictures of the process.

Thread that conducts electricity is really fun!

|

| Here, the big battery is sitting on top of some conductive thread, so its negative side is touching the thread. I'm holding a small loop of the thread around the negative prong of the LED. Now I have half a circuit. |

|

| I complete the circuit by touching the positive prong of the LED to the positive side of the battery, et voila! |

Overall, the course has given me a lot to think about, including concepts I didn’t touch on in this post. It briefly discusses the “maker” education theory of going beyond constructivism (mentioned in my last post) to constructionism-- actually constructing things as part of play or learning. It also mentions deconstruction as a learning activity: taking things apart to see how they work and how they were made. One of the interviewees said something that particularly resonated for me: We don't just want to design creative technologies. We want to design technologies to let other people do their own creative designing and creating and expressing.”

P.S. For anyone considering the course whom this is relevant to, it’s mostly videos with some reading, and the videos aren’t captioned, but they are transcribed.

Comments

Post a Comment